Impingement, hip impingement, FAI… It has lots of names.

It is unfortunately, NOT uncommon in hockey goalies.

It’s often present, but asymptomatic. I other words, you might have hip impingement and not feel any pain at all.

Click on the image above to download the entire report so you can read it on the go… or share it with someone who needs to know this stuff.

And I fear that the prevalence in hockey goalies has not yet peaked. I fear that by the time it reaches that peak where goalies, coaches, parents and strength coaches start to take it seriously, it will take years to turn the tide.

The problem is this… for a lot of goalies, it is an over-use injury. It is cumulative trauma, which means that it feels fine, it doesn’t hurt, but it is there and it is getting worse over time. You don’t notice it until you start to lose function or get pain, until significant damage has been done.

Even when you start to get symptoms you might not recognize them.

Ever ‘tweak’ your groin, with a specific movement, but then it is fine a few minutes later? That is not a muscle strain. Your muscles won’t bounce back that quickly. If you “tweaked” it enough to give you pain, you will have some residual stiffness or discomfort for at least a day or two.

What I think you are feeling is your femur smashing into the socket of your hip joint – that will give you a little ‘ouch’.

Are you scared?

I don’t mean to scare you… but I want you to take it seriously.

This is the type of thing that keeps me awake at nights (literally) and I wouldn’t mind if you cared enough about your hips and your longevity as a hockey goalie that you lost a few nights sleep worrying about it too.

So here it is, the comprehensive guide to hip impingement in hockey goalies

You know I have been working on this article for months – I feel like I am back in Grad school working on my Master’s thesis (okay not quite that bad… no scary examination committee). My goal is to present scientific research, published case studies and some of my experience from the last 25-years as a trainer working with athletes from all sports.

I am NOT an orthopaedic surgeon, a medical doctor nor a physical therapist. The thoughts/advice in this article are not a substitute for their expertise.

I am a certified exercise physiologist who specializes in training hockey goalies. I do have five years of experience working as the exercise specialist at the renowned Fowler Kennedy Sport Medicine Clinic at Western University and about 15 years working with goalies under my belt.

If your hips hurt, get them checked out. If your hips don’t hurt, read on… please!

You are welcome to disagree with anything in here. You are welcome to ignore it, I hope you don’t.

Some of this will be science-y; very science-y.

I am not trying to dazzle you, but it is complicated, there are many factors and forces at work. These are the things I consider when I create new exercises and workout programs for you and I want you to appreciate that it isn’t just a matter of ‘working out’ or doing some ‘cool stuff’ in the gym.

Here’s how we will flow through it:

1) What is FAI?

2) What are the symptoms?

3) How is it diagnosed?

4) How do you fix it?

5) How do you prevent it?

What is FAI?

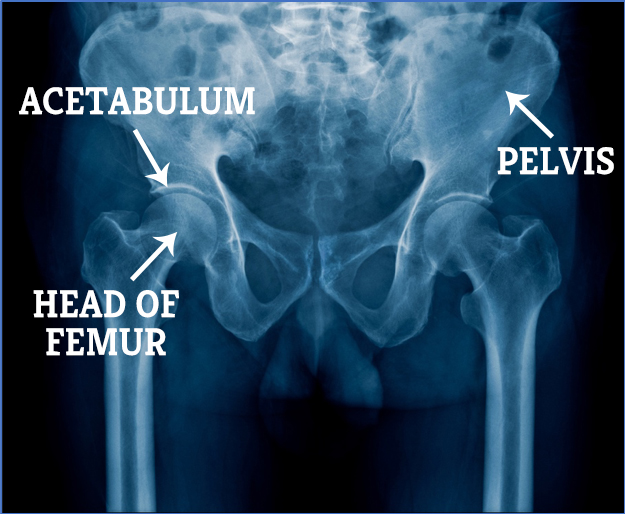

FAI is an acronym that stands for FemoroAcetabular Impingement. If you remember your undergrad anatomy class it makes sense – it is an impingement (or pinch) between your femur and your acetabulum… simple eh?

Let’s take it back a step…

Your hip is a ball and socket joint. The ball part is attached to your thigh bone (your femur). The socket is part of your pelvis, and that area that forms the socket is called the acetabulum.

So far so good right – anatomy is easy…

Why do you get that pinch in your femoroacetabular joint (your hip)?

There can be a few reasons…

Cam Impingement – the ball of your femur is mis-shaped so it rubs on the socket

Pincer Impingement – the rim of the acetabulum is mis-shaped so it rubs on the ball

Mixed Impingement – a little bit of both above

Before we continue, I want you to appreciate that not everyone has a perfectly matching ball and socket right from birth. You can have a bit of a mis-shaped ball or socket. You can have an acetabulum that sits at a bit of a funny angle (dysplasia). If you aren’t a hockey goalie, you might never notice it.

I don’t know if there are goalies who have such perfectly shaped femoroacetabular joints that they are immune to hip impingement.

I do know that if you have a bit of hip impingement and you keep forcing your hips into that impingement position over and over, you will make it worse.

Think about it like this. If you have a job shoveling all day long, what happens to your hands? You put a load on those tissues right? In response they sustain trauma, in this case it is in the form of blisters (your hip joints don’t develop blisters, but they sustain microtrauma). Then what happens over time? You develop thick callouses don’t you?

You aren’t acutely aware that your calluses are getting thicker and stronger month after month, but they do.

The same thing happens in your hip joint. In fact there is even a “Law” about the adaptation called Wolff’s Law Of Bone Formation which states:

“bone grows and remodels in response to the forces that are placed upon it in a healthy person. After an injury to bone, placing specific stress in specific directions to the bone can help it remodel and become normal healthy bone again.”

If you are healing a broken bone, that is exactly what you want.

If your bone is adapting to chronic micro-trauma and developing bony calluses in a confined space (like your hip joint), that can be a problem.

Now you have more tissue trying to move in a space that is already restricted, which leads to more trauma, which puts more compression and shear on the tissues in the hip joint like your articular cartilage and the labrum.

BACK UP… What is cartilage? What is labrum?

Great question, glad you asked.

CARTILAGE is kind of like synthetic ice – it is a slippery material that covers the surfaces of your joints that rub on each other (called the articular surfaces). Your acetabulum will be covered by cartilage and so will the head of your femur.

It helps the surfaces slide past one another and it gives some shock absorption to the joint and offers some protection to the underlying bones.

Like synthetic ice, it is fairly durable, but it is susceptible to wear and tear over time. It can get worn down or torn.

Premature wear and tear of the cartilage will lead to premature osteoarthritis in the joint. Osteoarthritis is non-reversible. You can wear away enough cartilage that you have “bone on bone” arthritis. Not good, this will lead to a hip replacement at some point.

The LABRUM is a ring of cartilage that attaches to the rim of the acetabulum. It also helps cushion the joint and helps hold the head of the femur in the socket like a gasket. It can also get pinched, worn down or torn.

I guess I should also mention the joint capsule which is a strong, fibrous connective tissue sock that encases the joint and delivers a ton of information to the brain about the position of the joint, the load on the joint, etc. It also contains the life-blood of all synovial joints, synovial fluid. This is what bathes the joint to provide nutrients and lubrication to the cartilage.

BONUS CONTENT: View the video below for a quick video explanation of FAI

Now that we have that out of the way, let’s continue…

What are the Symptoms of FAI?

The symptoms of FAI can include (and please don’t panic if you have one of these – there are lots

of reasons you could have these symptoms):

- Chronic hip pain

- Chronic groin pain

- Intermittent pain in the hip or groin

- Loss of range of motion in the hip

- Pinching in the hip (typically in the front and/or toward the groin)

- A ‘block’ feeling in the joint (like it just won’t go)

- Catching or locking in the hip joint

To me, I get a little concerned when a goalie describes a long standing ‘groin strain’ where there was no mechanism for a groin strain. When you actually strain your groin (or hip flexor), you do something and feel an “OUCH”. You can tell me “I reached for the puck with my leg and felt pain”.

A strain is not “I don’t know when it started”.

This could be tendonosus, pelvic misalignment, FAI or a number of other things, but not a strain,

so please don’t dismiss it.

How Is It Diagnosed?

A physical therapist, sport medicine doctor or orthopaedic surgeon will be pretty good at picking it up on physical exam. There are a few movements that put you in the impingement position, so if they put you in that position and it reproduces your discomfort, they will be suspicious of FAI.

BONUS CONTENT: I show you the positions they look at in the video below (& give you a quick SELF-EVALUATION to try)

Again, this DOES NOT mean you need surgery. But it does mean that you need to figure out what is going on.

X-Rays, MRI or CT are used to look at the ALPHA angle and if the angle is greater than 57 degrees and you are experiencing symptoms, then the chances are that cam impingement is causing the pain (Barrientos et al. 2016) and the surgeon might want to do something about it.

BONUS CONTENT: this video shows you exactly how that is done

How Do You Fix It?

Hopefully the first step in your recovery is a course of physical therapy with someone who has experience working with impingement. This can bring amazing results and even save you from surgery.

A six week course of physical therapy should give you some good symptom relief; you will not be cured, but you should be experiencing some encouraging results. In fact a case report published in the Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association detailed the “conservative management” (i.e. physical therapy vs. surgery) of a 22-year old former OHL goaltender who was forced to retire from competitive hockey due to hip pain.

After 6-weeks of consistent and diligent physical therapy he was pain-free at rest and during daily activities including exercise. After 8-weeks of treatment he was able to return to the ice without hip pain, eventually building up to three games per week in competitive men’s league hockey.

In a study by a group including orthopaedic surgeon Marc Philippon, athletes were giving a 6-week course of physical therapy prior to surgery. Again, not that you will be ‘cured’ in 6-weeks, but if you are getting significant improvements with conservative management, then you can spare yourself from surgery.

If surgery is the path you need to take, then it will likely be an arthroscopic procedure rather than the more invasive open procedure that used to be the standard.

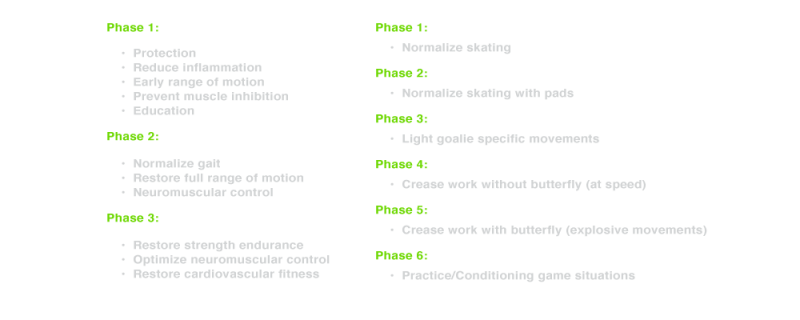

Philippon et al. (2013) did a great job outlining their 6-phase post-operative progressions back to the ice, with the goal of a return to play after 16-weeks.

I am not going to go into the step-by-step breakdown because:

1) This is not a “how to rehab your own hip after FAI surgery” article

2) Based on my experience the recovery is different for every goalie, so you need to work with a great physical therapist during your initial rehab.

But the take home message is this; it is a progressive program based on competency, which means if the goalie was not able to perform phase one tasks with competency and without pain, they did not move on to phase two.

Off-Ice, the goals of the phases are:

These are PHASES – – not days.

You cannot go on the ice one day and skate, the next day skate with pads, the next day do goalie specific movements and be back to games in 7-days. It is a progression that takes place over the course of 16-weeks (or more).

How Do You Prevent It?

This is where I get really excited, because if we can minimize it for most of you and even prevent it for some, that is a worthy goal.

Let me hop on my soapbox for a second if I might to chat about something that bugs me big time… the idea of “injury prevention exercises”.

It is a term I have used in the past, but what does it mean? When you say you need some injury prevention exercises for your off-ice program, is that opposed to ‘injury inducing exercises’?

When I hear ‘injury prevention program’, I think, “oh, you mean a properly designed off-ice training program?”.

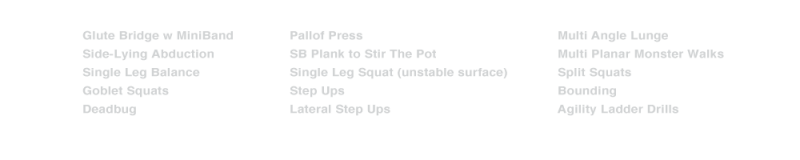

You don’t do workouts to help you build strength, speed, stamina… and then do workouts to reduce your risk of FAI. You should be doing a comprehensive program that develops you as a goalie; a program that delivers the qualities you need on the ice including hip mobility, strength, power, stamina – – all of it.

When I look at the exercises used to help the former OHL goalie return to the ice pain-free after 8-weeks, I am pleased to see so many of the exercises that you members of the Shutout Academy and Turning Pro Coaching program will recognize such as…

Okay – – off the soap box now, let’s continue…

Naturally, I see off-ice training as a huge part of keeping you on the ice and keeping your FAI at bay. If exercise therapy can help you avoid surgery and resolve your symptoms, then what if you started working on those things as part of your regular off-ice training program BEFORE you have symptoms?

In a study of 74 young hockey players (skaters and goalies) by Brunner et al (2016), 68% had FAI related bony deformities based on MRI results; only 22% were symptomatic and the results showed no difference in hip strength, range of motion, nor on-ice physical performance.

Again, this highlights the fact that you won’t know you have it until it is a problem, that’s why I believe it should be a consideration for goalie coaches and organizations starting from a young age.

At a young age, while goalies are growing and developing I am not convinced that ‘goalie specific’ off-ice training to reduce the impact of the forces on the hip is the best solution. Add to that the misconception by many coaches and trainers that ‘goalie specific’ off-ice training includes dropping into the butterfly, the splits and other high speed movements into some of the awkward postures you see goalies perform on the ice and you can see how this could do more harm than good.

I do think it is worthwhile looking at ways to minimize the wear and tear on the developing body.

A study by Whiteside, et al (2015) looked at the implications of on-ice movement in mature hockey goalies. On the surface, it looks like the butterfly position is the likely culprit of wear and tear to the joint. What they found was that hip internal rotation (rotating the front of your thigh inward – as a goalie would when performing a butterfly) was the most extreme motion exhibited by hockey goalies (compared to the end range of motion), that part makes sense.

The surprising part is they found that the peak magnitude for internal rotation at the hip occurred when the goalie was decelerating by shaving the blade of the skate across the ice as they would when decelerating from a t-push after moving from their post to the top of the crease on a diagonal.

Can you picture that motion where the thigh is rotated inward relative to the pelvis?

BONUS CONTENT: Here is a video showing you exactly what I mean

The researchers also concluded that:

“repetitive end-range hip internal rotation may be the primary precursor to symptomatic FAI in hockey goaltenders and provides the most plausible account for the high incidence of FAI in these athletes.”

And bear in mind, this data was collected prior to the Reverse VH (RVH) technique being introduced.

How do you reduce wear and tear?

This is a great question and I turn to baseball for the answer. I see a hockey goalie’s hip and knee joints very much the way I see a baseball pitcher’s shoulder and elbow joints respectively. Both are asked to do things that they were never designed to do.

I think the goalie has it worse than a pitcher, although the hip is a more stable joint than the shoulder, a pitcher is not landing with a magnitude of his/her body weight on that joint repeatedly. In his doctoral dissertation CCM biomechanist Ryan Frayne measured a ground reaction force equal to 1.45 times bodyweight when dropping into the butterfly.

In baseball they use pitch counts and there are several pitchers on each team.

This has not eliminated shoulder and elbow injuries in baseball players, but will it reduce wear and tear? Does it force some kids to rest their shoulder when they would choose to continue if they could… because remember “it feels fine”.

Should there be ‘butterfly counts’ in practice for goalies? Not a bad idea since in a game a goalie might do 50-70 butterflies, but in practice (or even warm-up) they can record over 200.

How many butterflies have your seen young kids do over the course of a week-long goalie camp. How many times have you heard a coach tell the goalie to drive their pads into the ice and to make that satisfying ‘THUMP’ sound that is somehow supposed to indicate a quicker goalie.

Newsflash… and this will upset some of you (a lot), but here we go… “Driving” your knees to the ice does NOT get you into your butterfly faster. I am sorry because I agree that you should be able to drive your knees and beat the puck. But biomechanics and physics disagree.

Think of it this way, if you are standing straight up and you want to crumple into a heap on the ground, can you somehow ‘pull’ yourself down into a crumpled mass faster? No, you can’t – you can try it if you want. You may make more noise if you pull your feet off the floor under you before you free fall to the floor, but you won’t go faster.

Anyway, back to the article…

How many reps of t-pushes? RVH? Double knee recoveries?

Based on Ryan Frayne’s data, butterfly on its own did not take goalies to their limit of passive hip internal rotation but did exceed the active hip internal rotation limits. However, the impulse used to initiate a double knee recovery took the goalie into more hip internal rotation than goalies who used a single knee recovery. Double knee recovery also took the goalie into more of a hip internal rotation/flexion position, which increases the likelihood of impingement.

BONUS CONTENT: Here is the difference between passive and active hip internal rotation

As I showed you in THIS video, when a practitioner wants to put you into an impingement position to see if it replicates your hip pain, they take you into hip internal rotation (butterfly), hip flexion (forward bend at the hips) and adduction (pulling your knees together to close the 5-hole), that is the aggravating position. That is what you do for your sport.

Dr. Frayne concluded that:

“The repeated combination of compromised body positions and large transient forces are environmental factors that are believed to contribute to the high incidence rate of intra-articular hip injuries in goaltenders” (P.31)

It all adds up.

Now, what happens if this young goalie never gets time away from the ice? What if they are constantly putting internal rotation forces through their hips while they grow and develop?

I am going to share a suspicion I have (I hope it is wrong)…

I am suspicious that goalies who have grown up with the butterfly, t-push and now RVH will grow up to have a torsion of their femur. By that I mean that their femur will be twisted along the length

into a more internally rotated position.

BONUS CONTENT: Below is a video showing exactly what I mean and why I think that

Is this going to be a bad thing? I guess we won’t know until this generation of goalies is older, but what about this idea?

What if there were three goalies at every practice?

This allows the goalies get better quality of training on the ice because a goalie’s heart rate data from practices in NO WAY resembles the goalies heart rate response to games. I fully appreciate that you all want to maximize your time in the net, but stick with me here.

You know how I am always telling you not to go for a long run. You know how I want you to train like a repeat sprinter? Well, you don’t get that in most of your practices, even though it is what you need to be successful in games.

The physiological element is a topic for another epic goalie training article, so I will leave it for now, let’s get back to the hips.

Having three goalies vs. two at every practice will help re-distribute those butterflies, t-pushes and RVHs

and in theory, each goalie would decrease their volume by about 16%. Let’s say that goes from

200 butterflies to 168 per practice.

If there are just two practices per week between September and the end of February (so pretty conservative estimates), that is a reduction of 1,664 butterflies per season. And how about if kids had 3-weeks completely off the ice at the end of the season and maybe three more weeks away from the ice throughout the rest of the year. Will that make a difference to the long-term health of a hockey goaltender’s hips? I don’t know. Nobody knows because no one has tried an intervention like this yet.

And this isn’t just a reflex response to try and protect those cute wee goalies. It is a high performance issue too. I don’t have definitive numbers, but most of the goalies I see getting surgery for FAI are 18-22 years of age (some younger and some older).

That means they probably started feeling symptoms when they were 16/17 – they ignored it and tried to play through it for a couple years and then finally were so functionally disabled by it that they had no other choice but surgery.

Hands up if you are a goalie who thinks missing most of a season at the age of 18-22 is

great for your development?

Exactly. No one wants that.

We won’t know for sure the BEST way to minimize the wear and tear on your hips until different interventions are studied scientifically. Often that research is driven by what happens in the real world first. Someone creates an intervention that seems to work, then science gets involved and they try to figure out if it does work, how it works and how to make it better.

But here is what I hypothesize:

1) Limit the volume of reps for young developing goalies with three goalies at practices and at least 3 continuous weeks off the ice during the off-season.

2) When goalies start their off-ice goalie specific hockey training there should be an emphasis on developing strength and stamina in the stabilizers of the hip, safely developing functional range of motion in the hips and teaching efficient/effective movement patterns.

BONUS CONTENT: THIS SIMPLE 14-DAY MOBILITY PROGRAM IS THE PERFECT PLACE TO START… BUT IF YOU FEEL PAIN OR A BLOCK WITH ANY OF THE DRILLS, LEAVE THAT EXERCISE OUT – MAKE SURE YOU READ THE ENTIRE INTRO BEFORE YOU GET STARTED – JUST CLICK THE BOX BELOW

Okay, that’s it and I could continue, but for those of you who have stuck with me thus far, I told you it would be epic 🙂

I probably raised as many questions as I answered; GOOD, because it is that complicated.

But like any big question, you hypothesize an answer based on the evidence on hand and give that a try, then you reflect on the results, you keep what is working, you make some revisions and keep testing.

That’s how we make progress.

ARE YOU READY TO BE THE BEST YOU CAN BE? Click below to access a step-by-step blueprint for mobility training

Here are the research articles and case studies referenced in this article:

Conservative management of an elite ice hockey goaltender with femoroactabular impingement (FAI):

a case report. MacIntyre, K et al. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 Dec; 59(4) 398-409

Ice hockey goaltender rehabilitation including on-ice progression, after arthroscopic hip surgery for femoroacetabular hip impingement. Pierce, C.; Laprade, R.; Wahoff, M.; O’Brien, L.; Philippon, M. JOSPT March 2013; 43(3) 129-141.

Prevalence and functional consequences of femoroacetabular impingement in young male ice

hockey players. Brunner et al. Am J of Sports Med. Jan 2016; 44(1) 46-53.

Femoroacetabular impingement in elite ice hockey goaltenders: Etiological implications of on-ice hip mechanics. Whiteside, et al. Am J of Sports Med. July 2015; 43(7) 1689-97.

The effects of ice hockey goaltender leg pads on safety and performance. Frayne, R. Thesis.

The University of Western Ontario, Graduate Program In Kinesiology. 2016

Is there a pathological alpha angle for hip impingement? A diagnostic test study.

Barrientos, et al. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2016 Aug: 3(3): 223-228.